In 2002, a vast expanse of ice smothering a remote Antarctic coast cracked up and vanished into the sea, creating open water along the shoreline for the first time in thousands of years including a new, nameless inlet.

That 9-mile (15 km) long bay of the Weddell Sea on the Antarctic Peninsula was formally named the “Vaughan Inlet” in 2008, in honour of Professor David Vaughan, a pioneer in understanding the breakup of ice shelves and the impacts of climate change on the frozen continent.

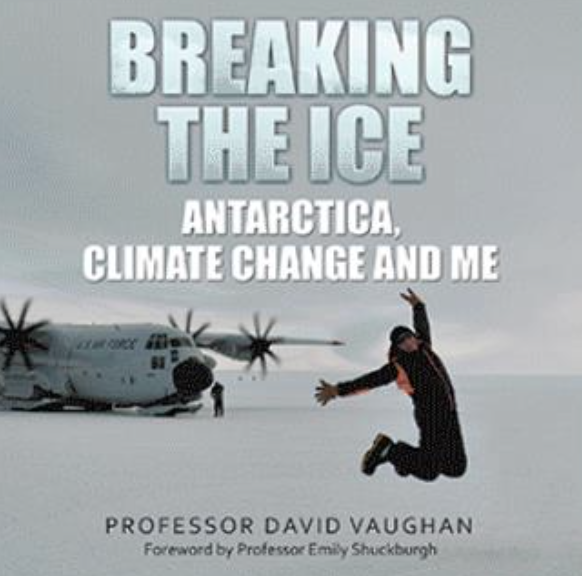

David, of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), passed away last year and left a mesmerising memoir that has just gone on sale: “Breaking the Ice: Antarctica, climate change and me”.

David documents his scientific breakthroughs along with the joy, frustrations and humour of living weeks in tents on the ice, often trapped in blizzards for days. He has advice for scientists: be more outspoken when you know about the catastrophe of global warming. He also tracks his struggle with what proved a fatal cancer.

Even that illness did not dim his sense of humour: he writes of a garden gnome secretly sent back and forward disguised as a tempting gift on flights between U.S. and British scientists in remote parts of Antarctica: once stashed inside a box of wine, another time even baked into a loaf of bread. You can imagine the sense of disappointment on opening those “gifts”.

Read the book! I’ve been honoured to have a small role in a team, led by David’s widow Jacqui with brilliant editing orchestrated by Linda Capper, formerly at BAS, to help the book to publication. It’s a thrilling, fond insight into a continent that was only first seen by mariners two centuries ago but whose thaw will redraw coastlines around the world as sea levels rise.

In 2009, when working as environment correspondent at Reuters News Agency, David accompanied my former colleague Stuart McDill and me on a nail-biting BAS flight to another ice shelf, the Wilkins, on the other side of the Antarctic Peninsula just weeks before it shattered and broke up.

When David got out of the tiny red Twin Otter plane onto the trackless ice he jumped and danced with happiness – typical of his infectious enthusiasm. It was the best imaginable assignment, and I’m proud we stayed friends.

The naming of the Vaughan Inlet, near a place called Shiver Point, came after the collapse of the Larsen B ice shelf in 2002, when around 3,250 square kilometres (1,250 square miles) of ice shelf were lost in a few weeks.

In typical style, David writes: “The area of Larsen B ice shelf loss over the summer of 2002 was a little less than that of Cornwall, and a little larger than Rhode Island. Glaciologists and journalists have made something of a sport of inventing the ridiculous comparative units for the area and volumes of ice-shelves and icebergs. The ‘Olympic swimming pool’ is well used, as is ‘Manhattan’, and my personal favourite, ‘Wales’.

The book is available from AuthorHouse, Amazon and other booksellers. Royalties will go to a special bursary for science, technology, engineering and mathematics students at Churchill College, Cambridge.