Sea levels could rise by more than 15 metres by 2300 in the most extreme case if man-made greenhouse gas emissions keep rising and the vast ice sheets on Antarctica and Greenland start to break up, according to a grim new report by the world’s top climate scientists.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on Monday said that global warming is getting ever more severe and that the impacts will last for centuries, causing more heatwaves, floods and wildfires, and melting ever more ice.

“Many changes due to past and future greenhouse gas emissions are irreversible for centuries to millennia, especially changes in the ocean, ice sheets and global sea level,” it says.

“The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable,” UN Secretary-General António Guteres said, adding the report marked “code red for humanity”.

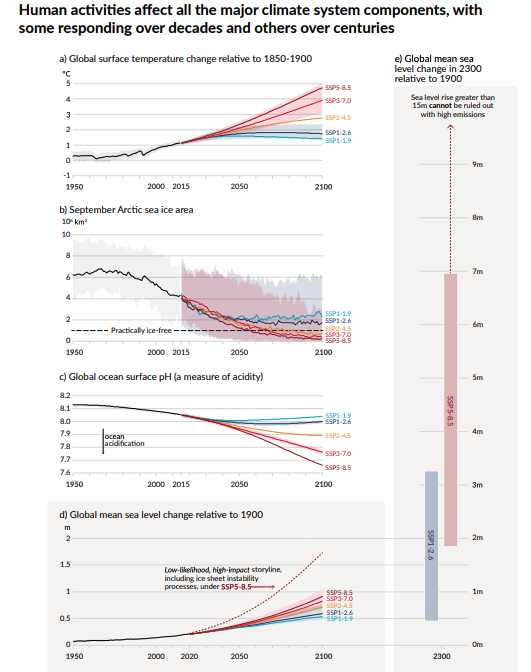

For sea level rise, the main scenarios (pink bar in graph below, right-hand side) show a gain of between about two and seven metres by 2300 with high emissions, above the range reported just two years ago by the IPCC in a special report about melting ice. And Monday’s graph also includes a shocking note for 2300: “sea level rise greater than 15 metres cannot be ruled out with high emissions.” Even this century, sea levels could gain by almost two metres on that worst track.

The underlying data show that could happen in the worst case if ice shelves floating on the sea around Antarctica break up and vast ice cliffs begin to collapse into the sea.

But all is not lost. In the best case (blue) with deep cuts in emissions promised by governments in the 2015 Paris Agreement, the IPCC shows that seas could rise anywhere from about 0.3 metre to about three by 2300.

Rises of several metres would mark an apocalyptic future, redrawing maps of the world and forcing migration by millions of people. Fifteen metres is roughly the height of a four-storey building, and such a rise would swamp massive land areas around the globe – about 680 million people, almost a tenth of the global population, live within 10 metres of sea level around the world.

Guðfinna Aðalgeirsdóttir, an IPCC lead author and professor in Geophysics at the Faculty of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland, said the report was the first by the IPCC to try to put numbers on “low probability, high impact events” like the collapse of Antarctic ice cliffs.

She said she hoped that the report would spur more action “so that the reduction of emissions will happen very fast” towards carbon neutrality by 2050.

Among alarming signs, she noted that “The combined contribution of Greenland and Antarctica is four times greater” in the period 2010-19 than in 1992-99.

Another IPCC document sent to governments about the history of sea levels notes that ocean levels were about two to eight metres higher about 125,000 years ago when slight shifts in Earth’s orbit caused a rise in temperatures to around current levels. And it said that seas were 5 to 25 metres higher about three million years ago in another natural warm period when temperatures were higher than now.

“Insights from such studies may help to reduce the large uncertainties around estimates of global sea level rise by 2300,” it says. It says sea level rise by 2300 could be “as much as 16 m higher than 1850-1900 (in a very high-emissions scenario that includes accelerating structural disintegration of the polar ice sheets).”

And the IPCC says that human greenhouse gas emissions, led by the burning of coal, oil and natural gas, have already committed the planet to wrenching shifts. Water in the oceans is expanding as heat penetrates ever deeper into the waters, and meltwater is pouring in from glaciers and ice sheets.

“Regardless of the emissions scenario, it will continue,” Aðalgeirsdóttir said.